If you use proper breathing techniques and stand with the correct posture you can increase the power and appeal of your voice. What we’ll be looking at in this article is what’s called diaphragmatic breathing — and the body positions that allow you to accomplish it. These techniques are nothing exotic or esoteric – they’ve been used by opera singers and other voice professionals literally for centuries.

Maybe the reason that they’re not more commonly adopted is that they seem exotic. For example, when you discuss the concept of “diaphragmatic breathing” it sounds as though you are going to completely alter the way you process air, or use a different organ, and that’s not the case.

What you will do is use some techniques particularly valuable for performers.

I think I know what you are thinking: You’ve been breathing fine for many years now and you don’t need somebody to tell you how to do something that comes as naturally as, well, breathing.

In point of fact there’s a difference between what we somewhat condescendingly call “vegetative breathing” – meaning, breathing that performs the quite necessary task of keeping you alive – and diaphragmatic breathing. But all it amounts to is more actively engaging that sheet of muscle behind the whole process, the diaphragm.

More on that in a second, but first let me clarify that what we are talking about is nothing more than a method of breath control that gives you a bigger air supply and, more importantly, a steady flow of air for vocal support and power .

So…what is this mysterious “diaphragm?” It’s a sheet of muscle that covers the bottom of the breathing area of your chest. Moving it down sucks air in, and moving it up blows air out. It’s as simple as that. If you let the diaphragm do its work you can really get some power behind your voice.

The figure at the top of this article shows the basic anatomy of the diaphragm and chest area.

Where most people go wrong is that they equate taking a big breath with expanding their chest. But the chest is where the lungs are, and in point of fact lungs have nothing to do with expelling air. They’re just filters to get the oxygen out of the blood.

Take a look at the picture. See what I mean when I say that air support figuratively comes from the stomach? Throwing out your chest is actually counterproductive because it diverts your attention and effort away from the proper area to expand – the abdomen.

Expanding the abdomen runs counter to our perception of the perfect male and female physique, but put vanity aside for a minute and just allow your abdomen to expand when you breathe in. I mean, really breathe in. Get a full tank of air. In fact, while you’re breathing in feel your short ribs and chest and make sure they do not expand. Focus on letting the abdomen push out and down, and when you’ve got a full tank of air push up with it and you will feel and hear the difference.

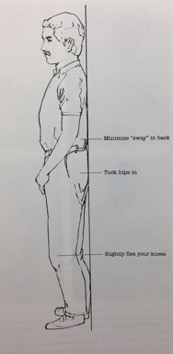

An appropriate posture makes this easier. Stand against a wall and keep your back fairly flat and your hips tucked in. Flex your knees just a little. This is a posture taught to me by David Blair McCloskey, a famous vocal coach who has worked with such notables as President John F. Kennedy, actor Al Pacino, and actress Ruth Gordon. McCloskey was an operatic baritone, and also taught this posture to opera singers.

Why does this posture enhance the voice? Simply because it allows for the freest expansion of the diaphragm.

There’s no mystery here: Take much deeper breaths, allow the abdomen to expand, making sure you don’t expand the chest or the short ribs, and push the air out from the diaphragm. Put your hand a little below the solar plexus and push in gently, aiding the process. You’ll feel what I mean. And more importantly, you’ll hear what I mean. Now that you know what that sensation feels like, replicate it. Practice it.

I know I sound like an infomercial salesman here, but I would be remiss if I didn’t say, “wait, there’s more!” But – there is more. Diaphragmatic breathing not only helps with voice production but also with relaxation. If you’ve ever engaged in any martial arts training you know that deep breathing from the diaphragm is often a part of the process. Mediation also involves deep, slow breathing.

Another benefit: Breathing more deeply and taking in a full tank of air forces you to slow down your rate of speech a little because you have to take time to breathe. Almost every speaker can benefit from slowing down a little.

And one more thing: If you take rapid, shallow breaths, you’ll sound nervous – even if you’re not. The simple act of forcing yourself to take less frequent, much deeper breaths makes you appear more confident. And when you appear more confident you set up a feedback loop with the audience and you actually become more confident.

So, let’s put it all together. This is a simple, straightforward process. It’s not always easy, because any new habit takes time to develop, but all you have to do is remember that your basic purpose is to produce a more powerful and more steady column of air. To do this, allow the diaphragm to expand. Don’t expand your chest. Expand the abdomen. Keep your back fairly straight and tuck your hips in to allow for full, comfortable expansion. When you breathe out, propel from beneath the solar plexus. To gauge the sensation, when you start out, put your hand a little under your solar plexus and push. You’ll feel and hear the difference.

That is the sensation you want. The voice coming from a deeper place. Take deeper breaths. Don’t let yourself run short of air. Keep the tank at least half full.

In sum – this is not an esoteric process. Just let that sheet of muscle really expand and involve that big muscle more directly in propelling your voice.

If you would like a free copy of my ebook on improving the voice, which contains illustrations of exercises useful for relaxing the vocal chain, click here: http://carlhausman.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Voice-Book-BonusCollateral.pdf

All I ask in return is that you sign up for my newsletter. See the box at the top of the page.

Also, for an exceedingly modest price, you can purchase my audiobook at Audible.com and hear some of the techniques in action. https://www.audible.com/pd/How-to-Develop-a-Powerful-Clear-and-Resonant-Speaking-Voice-Audiobook/B07HKZJWT6?qid=1538504342&sr=sr_1_1&ref=a_search_c3_lProduct_1_1&pf_rd_p=e81b7c27-6880-467a-b5a7-13cef5d729fe&pf_rd_r=HPWWTSAB57K4165CWNQG&